Cross-posted from ccafs.cgiar.org

Better management of agricultural risk today can help farming systems adapt to increased weather and climate extremes in the future.

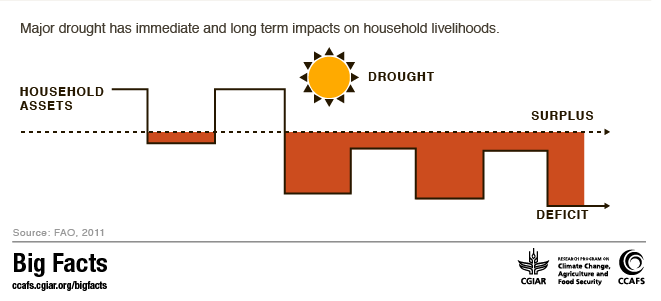

More extreme floods, storms and drought. Increased outbreaks of pests and disease. And even more uncertainty about what the growing season will bring. Climate change will likely heighten these risks to agriculture, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where adaptive capacity is already weak, threatening food, farming, and livelihoods.

Over 90% of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa is rainfed, leaving smallholder farmers in the region highly vulnerable to climate risk. This risk robs them of more productive opportunities and can devastate livelihoods in extreme years.

When climate varies dramatically from year to year, a farmer may be reluctant to invest in inputs such as fertilizer or better seeds that could increase productivity. Credit providers are also wary of lending to small farmers when risk is so high, which can leave farmers locked in a cycle of low productivity and poverty.

As water supplies decrease and become more erratic, risk management strategies must take on this issue and how it impacts crop yields and livelihoods.

Risk management solutions do exist, as part of a suite of climate-smart agricultural technologies. Weather index-based insurance is a financial innovation that allows smallholder farmers to access agricultural insurance, by overcoming the limitations of traditional loss-based payouts. It uses a weather index, such as rainfall, to determine payouts and these can be made more quickly and with less argument than is typical for conventional crop insurance.

As a complement to insurance and other climate-smart technologies, climate information services advise farmers about the upcoming growing season, from shorter-term weather alerts to seasonal climate forecasts.

With the protection afforded by insurance and foresight from climate services, farmers can more safely take advantage of favorable conditions by investing in agricultural inputs such as fertilizer or seeds, and take steps to avoid harm to their crops caused by extreme weather and climate conditions.

But each innovation faces challenges in scaling up, and more knowledge is needed about their effectiveness.

The Forum for Agricultural Risk Management in Development (FARMD) was created in 2010 to address this need, and build a network of risk management practitioners. Today, FARMD is a vibrant knowledge-sharing platform and community of practitioners, holding frequent webinars and annual conferences.

In its 2014 annual conference, to be held November 4-5, FARMD will examine the nexus between climate change and agricultural risks in sub-Saharan Africa, seeking to fill an important knowledge gap and improve understanding on the topic.

In collaboration with researchers and climate services practitioners, researchers from the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) have undertaken the first comprehensive analysis of climate services experiences in the developing world. In a new analysis, researchers offer key lessons for successfully delivering and scaling up weather and climate information and related advisory services for smallholder farmers.

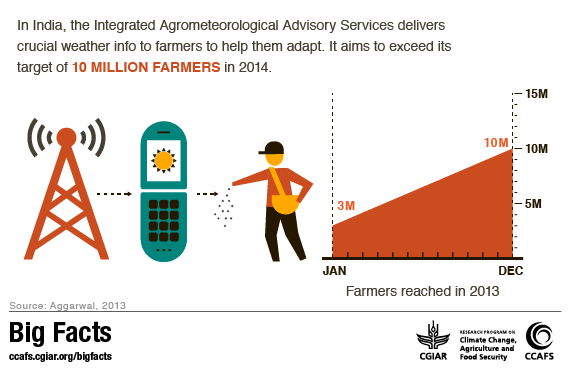

“This analysis shows that climate information services are a viable approach for supporting farmers in building climate resilience, especially relevant now as the IPCC shows that climate change is already having an impact in the developing world,” says Bruce Campbell, CCAFS director, who will deliver a keynote speech at the conference. “These tools and approaches, aided by rapid adoption of technologies such as mobile phones, have the potential to make an impact on millions of vulnerable farmers.”

“The wealth of experience in climate services provides opportunities for African countries to learn from one another and from good practices in other regions like South Asia,” says James Kinyangi, who leads CCAFS work in East Africa and co-authored the ‘Scaling Up’ study. In one example, the study reviews good practices in the case of India, which provides around 10 million farmers with agro-meteorological advisory services through diverse communications channels.

Kinyangi, who will speak at the conference about climate change trends and implications for managing agricultural risk, emphasizes that technologies and approaches need to fit the local context, and can make the most impact when used together.

For example, climate risk management encompasses technologies (e.g., flood or drought resistant crop varieties), institutions (e.g., weather index-based insurance), and climate information systems (e.g., seasonal climate forecasts).

“Together, these strategies promote better management of climate risk in agriculture in the near-term, and support building resilience to climate change in the longer-term,” said Kinyangi.